Latest News

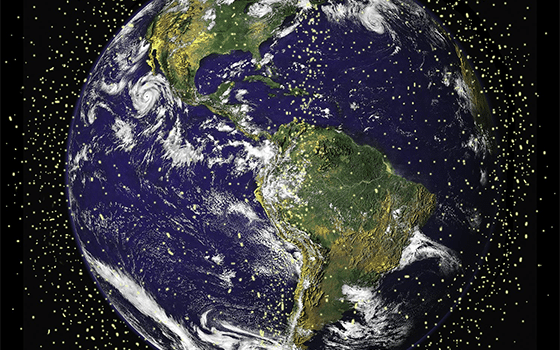

Rendition of orbital debris. Photo: NASA.

The academic community can and should play a larger role in tackling the issues of space debris and space situational awareness, according to Moriba Jah, an associate professor for the University of Texas’ aerospace engineering department. In an interview with Via Satellite, Jah said the aerospace industry must invest in “rigorous and comprehensive” scientific research in order to quantify and predict the behavior of objects in space and also enable long-term sustainability of space activities.

Prior to his current position, Jah worked as a space navigator for NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, as well as the director of the Advanced Sciences and Technology Research Institute for Astronautics (ASTRIA) under the Air Force Research Laboratory (AFRL). That experience, he said, opened his eyes to the obstacles that make addressing orbital debris so challenging.

“Our ability to measure and predict things in space is oftentimes quite poor. That points to our lack of knowledge and also our lack of understanding,” Jah said. “Without the proper investment in science to draw hypotheses and test those regularly, there’s just no way that we’re going to be able to address the problem.”

One of the biggest issues is that the technology, such as phased-array radars and electro-optical sensors, is still relatively limited, forcing organizations to track objects intermittently rather than continually. “We don’t have ubiquitous sensing, and thus the first step to increase our ability to monitor our geospace would be to create a global, common data lake for everyone to contribute to and exploit. When we want to assess any alleged event, we gather witnesses and evidence and weigh these to arrive at a conclusion. We need that for space traffic and space surveillance,” Jah said.

Moriba Jah, associate professor in aerospace engineering at University of Texas. Photo: University of Texas.

Moreover, Jah believes researchers can drastically improve the way we model orbiting objects. For example, U.S. Strategic Command under the Department of Defense has a catalog of more than 1,300 active satellites and thousands more pieces of debris. However, according to Jah, every object represented in that catalog is modeled as if it were a sphere, which is problematic for making precise predictions about the objects’ motion in space.

“Not everything behaves like a sphere, so for debris whose behavior is inconsistent with how a cannonball would behave in space, you won’t find it again. There’s no way to identify these things or track them. Part of the problem is how we represent these things,” he said.

To improve space situational awareness, Jah said ASTRIA has taken a lesson from biologists in how they quantify populations and understand their behavior. “Typically when people try to characterize the population of something, they go to individuals in that population, tag them, then track those individuals over time to see how they interact with the rest of their community, so to speak,” he said. ASTRIA is working to do the same — the equivalent of “tag and track,” as Jah put it — to better understand how satellites and debris behave in their various “habitats,” whether that be Low Earth Orbit (LEO) or Geostationary Orbit (GEO).

Jah believes the industry needs additional empirical data to guide the decision-making process before it can implement new regulations to address space debris. For example, he said, researchers can help establish a classification system to identify key distinguishing elements that affect how an object moves in orbit. “When we look at maritime, for instance, the way we regulate oil tankers is very different from kayaks and canoes. If you look at the roads, the way we regulate semi-trucks is different from Vespa scooters. Something similar needs to happen with space,” he said. “We need a taxonomy to classify things in space … so that regulations can be made surgically and sensibly for things based on the category they’re in.”

From the government perspective, Jah said he hopes to see more transparency and more investment in fundamental early applied research. Not only must the government make a concerted effort to declassify information that doesn’t need to be classified, he said, it must also form stronger academic partnerships. “There is no problem in the sense of getting people interested in solving these problems; the problem is in the level of funding. There’s little to no funding for academics to do this stuff and people aren’t just going to do it for free,” he said.

Transparency is important on the commercial side too, Jah believes, as it is in everyone’s best interest to share their observations and coalesce a precise, reliable body of knowledge. “Being able to monitor things as persistently as possible and making that monitoring global and transparent is key to furthering commerce in space,” he said.

Get the latest Via Satellite news!

Subscribe Now