Latest News

Japan and Canada are making significant changes to how their national space agencies operate, while Australia is examining whether there is a need for national space agency at all. Speakers from each had time to dig deeper into their respective countries’ space industry plans during the 33rd Space Symposium last week in Colorado Springs, Colorado.

Space in Japan

According to Shuzo Takada, director general of Japan’s National Space Policy Secretariat, the country has made a major shift in the goals of its space policy from the previous decade. Previously, Japan had banned all military use of space assets, limiting the industry to commercial and research purposes. Now, however, the country has established new laws on space development that place heavy emphasis on space security.

This is due in part to growing threats from countries such as North Korea and, as Takada put it, “space’s increasing importance in national security policy.” Defense-wise, Takada said Japan had largely focused on the resiliency of its space systems in the past. Now it’s taking a three-pronged approach: building resilient systems, but also taking measures to prevent incidents from happening in the first place, and emphasizing countermeasures in the event of an attack. All of these are “indispensible for mission assurance,” Takada said.

Shuzo Takada, director general of the National Space Policy Secretariat, at the 33rd Space Symposium. Photo Space Foundation.

Although Research and Development (R&D) currently eats up the majority of Japan’s space budget, Takada expects the amount of funds allocated toward space security to increase over time. He said that Japan plans to strengthen national security by using optical and radar observation to improve Space Situational Awareness (SSA), and by expanding cooperation with allied countries such as France and the United States.

On the civil side, Japan’s biggest short-term project is the completion of its Quazi-Zenth Satellite System (QZSS). The first satellite, Michibiki, launched back in 2010, and Japan plans to deploy the remainder of the seven satellites by 2023. As a Global Navigation Satellite System (GNSS), QZSS is designed to provide communications and also complement existing Global Positioning System (GPS) satellites by increasing accuracy down to the centimeter. The constellation will fly in an elliptical Geosynchronous Earth Orbit (GEO) to ensure at least one satellite hovers over Japan at all times.

Space in Canada

Not unlike Japan, Canada’s industry was largely built around its mandate for the peaceful use of space, said Canadian Space Agency (CSA) President Sylain Laporte. Any missions planned exclusively for national security are passed along to the military, which is part of the reason why the CSA is relatively small compared to other agencies such as NASA. Nonetheless, the CSA has been involved in a number of international space endeavors, including manufacturing instruments for the James Webb Space Telescope.

Because of the country’s geography, much of Canada’s space investments have gone toward Maritime Domain Awareness (MDA) and Earth Observation (EO) technology. “We use Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) to look at … these immense, vast agricultural fields. By feeding that back to the farmer he is able to optimize his yield,” Laporte said. The panelists agreed that strength in these areas should continue, fueled particularly by start-ups entering Canada’s maturing commercial space industry. “I see very rapid growth in the smallsat environment. That’s really good news for space agencies like mine where you try do as much as possible on a limited budget,” said Laporte.

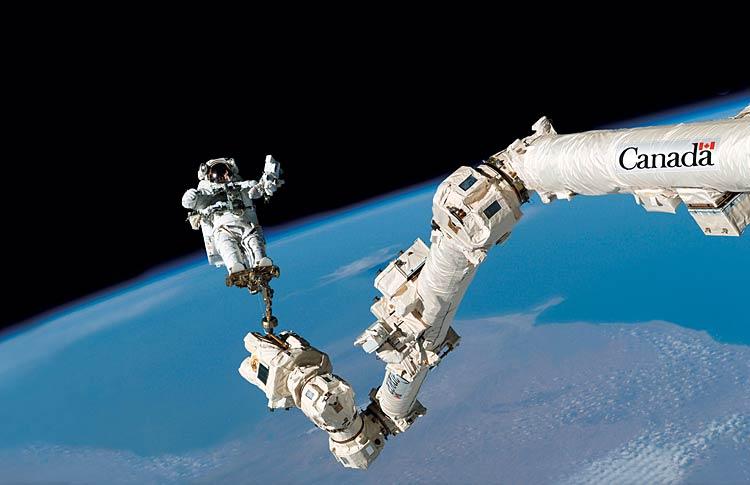

Astronaut Chris Hadfield attached to the Canadarm. Photo: NASA.

Laporte also highlighted Maritime Launch Systems’ (MLS) efforts to construct a new launch pad in Nova Scotia as a testament to Canada’s growing commercial prospects. “They have partnered with a company in the Ukraine looking at a medium capacity launch vehicle,” Laporte said. “They’re looking at reaching initial operating capability in the 2020-2021 time frame. It is entirely a commercial venture.”

Donald Osborne, president of MDA Information Systems, noted that the government of Canada has been very supportive of the commercial side of the industry and likely will continue to be. “The Canadian space industry is underpinned by strong relationships with the government. Whether you’re large or small you’ve used the CSA or government funding to be successful,” he said. “The secret for being successful in our industry is leveraging what you can do with government funding into the export market or commercial sales.”

According to Laporte, the idea of bringing new technologies to the international market runs throughout all of Canada’s space activities, on both the government and the commercial side. He stressed that Canada will continue to rely on its friends across borders to advance space capabilities. “The rapid growth and exciting opportunities that we’re seeing are being put into a context of international collaboration, and all of us are sharing our information to ensure we can leverage from one another. Humanity is going at this together,” he said.

To that end, Canada plans to contribute wherever it can to the international space community. Most recently, the government set aside funds for the CSA to begin preparing for the next Mars mission to modernize the satellites currently orbiting the planet.

Space in Australia

Meanwhile, Australian officials continue to debate the pros and cons of having a national space agency. Because there is no equivalent to NASA or CSA in Australia, research is typically done through the universities funded by the Australian Research Council, said Shaun Wilson, chief executive officer of Shoal Group.

This has led to a desire for governmental coordination across the industry, according to Russell Boyce, chair for space engineering at the University of New South Wales-Canberra. “Such an agency could be the vehicle to stimulate a mature Australian space sector,” he said. Nova Group co-founder Peter Nikoloff agreed, noting that it’s important to have an organization driving a national strategy for space. His vision is to have one central body governing everything from scientific research to national security to the growth of the commercial sector, each of which he said needs to be “equally balanced.”

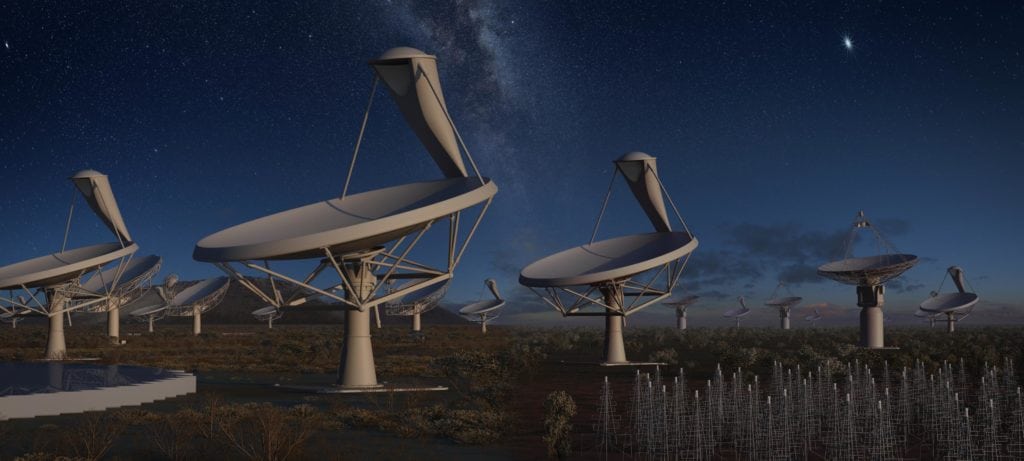

Rendition of the Square Kilometer Array. Photo: SKA Organization.

Anna Moore, director of Australia National University’s Advanced Instrumentation and Technology Center (AITC), said that despite the lack of a national agency, the Australian government hasn’t necessarily shirked its responsibility to fund science projects. In fact, it recently invested $300 million into the Square Kilometer Array (SKA), a next-generation telescope that will be built across Australia and South Africa. Still, there are gaps she hopes a national body could potentially address, such as funding for small missions run by students. “There’s no funding mechanism they can apply to that directly address space,” she said — and to make matters worse, they must also compete with established companies in Australia’s relatively large ground infrastructure sector. Moore said she hopes to see new funding sources in the next five to 10 years geared specifically toward young researchers.

Anthony Murfett, minister counselor of industry, science and education at the Australian Embassy in the United States, said that it’s important for Australia to first establish its strategic priorities before running headlong into creating a national agency. “I think what will really assist the government in determining its role and [how] we go forward is getting a good understanding of Australia’s competitive advantage,” he said.

According to Wilson, Australia has thus far chosen explicitly to focus on ground infrastructure and data processing, with space segment services typically provided commercially. That should function as a good starting point for the industry’s continued growth as NewSpace companies such as Sky and Space Global enter the arena. Overall, even without a national agency, the speakers seemed optimistic that commercial initiatives can help propel the Australian industry forward into the future, both in its niche of ground infrastructure and outside of it.

Get the latest Via Satellite news!

Subscribe Now