Latest News

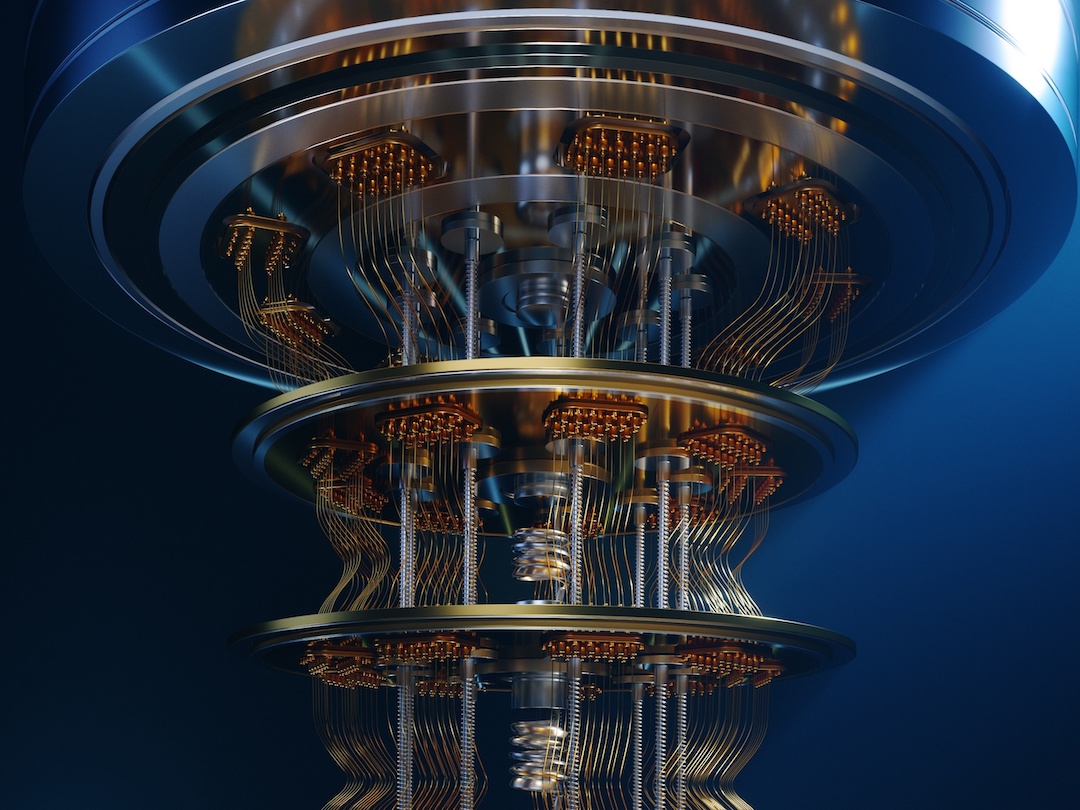

Quantum computer Photo: Via archive/Shutterstock

Emerging technologies like quantum computing and artificial intelligence create new threats to defend against, as well as new defensive capabilities for the commercial space sector, U.S. defense officials said at the recent CyberSat event in November.

Officials from the Space Force, the Air Force, the Marine Corps and the Pentagon highlighted their concerns about the runaway consequences of using cutting edge new technologies for the untrammeled development of offensive cyber tools.

James “Aaron” Bishop, the chief information security officer (CISO) for the Department of the Air Force, compared these technologies to the first Jurassic Park movie, in which Jeff Goldblum’s character observed that scientists were so busy trying to do something, that they never asked whether they should do it.

“That’s where we are,” he said. “We’re busy researching how to do it,” he said, referring to quantum-enabled cyberattacks. “What I’m worried about is, once they achieve it, it’s going to be unleashed on the world. And we don’t know what we just did. To me, that’s the real issue.”

Quantum computing would enable attackers to visualize and understand the vulnerabilities in an IT network much faster than they currently can, reducing the time the attacker has to spend in the network, moving around and mapping it, which today often offers the best opportunity to detect and expel them.

“If I can just [snaps fingers] and know all your vulnerabilities, I can come back another day and take you out. You will not have had any time to monitor me poking around your system, which is the way we catch you today,” Bishop said.

Precisely because of the risks inherent in such technologies, the Department of Defense is very focused on the issues of trust and trustworthiness when it comes to AI.

“Trust is a very dynamic entity,” said Kimberly Sablon, from the Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Critical Technologies.

Trust of a weapon or any other system incorporating AI means “justified confidence in the performance of that system,” Sablon said.

“Based on observable evidence, I know that this system is going to operate in a very reliable way, and, more importantly, consistent in how it’s executing the objectives that it was designed to — doing so in accordance with user defined goals and expectations,” she explained.

Earlier this year, Sablon noted, the DoD set up a special hub at Carnegie Mellon University’s famed Software Engineering Institute, bringing together AI researchers, DoD weapons testers and early technology adopters in the military.

The Center for Calibrated Trust Measurement and Evaluation, or CaTE, Sablon said, is figuring out metrics that can be used, in any given environment, to measure trustworthiness, risk and “all of the required metrics and even methods for observing those metrics, methods for correcting the system, should it start to deviate beyond its performance bounds.”

It was important to recognize the limitations of AI, Sablon said, especially in regard to autonomy. “The silver bullet is not always full autonomy. The silver bullet might be a lower tech or no solution at all, especially when we’re talking about the space domain.”

Complicating the equation is the U.S. competition with China and other adversary nations — creating concern that guardrails or regulation on U.S. research might hamstring its progress against adversaries who are less risk averse.

Bishop pushed back hard at the idea that the U.S. should refrain from research into potentially risky quantum applications, but argued more thought needs to go into the potential impact.

“I didn’t say we shouldn’t do so. We need to worry about when we release it, what are we releasing? We’re not spending any energy on that side of the equation. We’re only busy trying to … build this [quantum] computer. Once we’ve done that, we’re not really in control. That’s the situation we’re going to find ourselves in,” he said.

As with AI and other emerging tech, quantum is not one singular thing, Bishop stressed. People always think about cryptography when they hear the word quantum, and that threat is real. He said that “harvest now, decrypt later,” the concept in which an adversary captures encrypted communications flowing over the open internet in the expectation of being able to decrypt them with a working quantum computer, is already going on, he said.

“Algorithm agility is where we need to go,” he said, arguing that the advent of the quantum age means always being ready to reinforce encryption. The days of hard coding an algorithm into a piece of hardware and not worrying about it until the hardware is replaced are over. “We have to be able to change the algorithms on demand and be able to understand why we changed them,” he said.

But the ability of quantum computers to crack previously secure encryption algorithms is only one of many disruptive effects the development of the technology would have.

Quantum computing uses the weird physical properties of subatomic particles to power ultra-fast computation. Quantum sensing uses those same properties to measure, with extraordinary accuracy, phenomena like the Earth’s gravitational or magnetic field, or to track inertial movement.

Quantum sensing, several experts noted, will soon provide capabilities that replace or back-up GPS and other satellite-based position, navigation and timing, or PNT, services.

PNT has become essential to modern warfare because the guidance systems of unmanned aerial vehicles or UAVs, smart bombs, cruise missiles and other precision-guided munitions rely on it. But in a shooting war with a peer adversary, GPS is likely to be jammed or spoofed, making the development of back-up PNT technologies, including those based on quantum sensing a strategic priority for the U.S. military.

But quantum sensing technologies could also be used on satellite platforms, noted David DiEugenio, CIO for the U.S. Marine Corps recruiting enterprise, where their extraordinary precision and sensitivity could provide new use-cases for the warfighter, like distinguishing between friendly and enemy forces.

“There’s a great opportunity to be able to take advantage of satellite platforms to help support those efforts,” he said. “I know where I am. I don’t know where the bad guys are. Quantum sensors that are based on satellite platforms offer the opportunity to better do that positive identification with precision,” he explained.

Satellites could also employ the third type of quantum technology, in addition to computing and sensing — communications, said DiEugenio.

Quantum holds the promise of secure communication by exploiting a phenomenon known as superpositioning, where a quantum particle called a qubit can be both a 1 and a 0. But observation, such as eavesdropping by hackers or online spies, collapses the quantum state. The qubit becomes either a 1 or a 0. The collapse reveals the compromise of the communication.

By employing quantum communications, DiEugenio said, satellites “could help to safeguard the delivering of that [PNT] information and sharing that situational awareness.”

But quantum communications also have an offensive side, highlighted earlier this year by Chief Master Sgt. Ronald Lerch, the senior enlisted leader for the Intelligence Directorate of U.S. Space Systems Command.

Earlier this year, Lerch outlined what he called “our nightmare scenario.”

He said at an industry event it was the prospect that the Chinese People’s Liberation Army, or PLA, could use secure quantum communications to provide command, control and communications, or C3, to its forces anywhere on the globe from an inaccessible location in the vast blackness between the Earth and the Moon, known as cislunar space.

“The Terminator that stalks us in our dreams… is this idea that the PLA will have a quantum capability that’s parked out there in cislunar space doing C3, and we can’t see it, we can’t reach it, we can’t get access to it. And that’s terrifying,” Lerch said.

In AI, the nightmare scenario is an adversary unconstrained by the moral and legal guardrails that limit U.S. use of the technology.

“The Chinese look at space as a very complex and very dangerous environment,” said Rudolph “Reb” Butler, the senior chief advisor to the Chief Technology and Innovation Officer of the U.S. Space Force, “They’re very comfortable using AI and taking the human out of the loop and putting the robot into the loop on orbit.”

By contrast, the Space Force, which is already employing AI for a lot of small automation tools takes the position that “the human is still accountable for how the tool is employed,” Butler said.

Space situational awareness, or SSA, which is one of the U.S. Space Force’s critical missions needs AI to help human analysts sift through the huge amount of data required, he said. This is a critical issue because figuring out quickly what happened to an asset on orbit is both extremely difficult and vitally important.

“Will we be able to handle the complexity of recognizing a hazard, a natural environment problem, versus an attack versus a feint versus a spoof?” he asked.

The Space Force is working with its partners to alleviate the cognitive burden on humans of dealing with SSA data through automation.

“There’s a lot of work to be done,” Butler said. “A lot of people see AI as the easy button. It’s not an easy button. When we talk about autonomy, it makes it even more and more complex.”

Stay connected and get ahead with the leading source of industry intel!

Subscribe Now